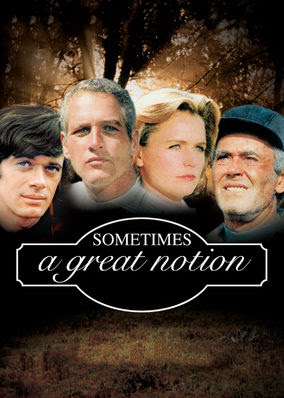

From Universal

Directed by Paul Newman

Starring

Paul Newman

Henry Fonda

Lee Remick

Michael Sarrazin

Richard Jaeckel

Linda Lawson

Joe Maross

Cliff Potts

I've always enjoyed spending a couple of hours with the Stamper family, kings of Oregon's timber country. That is not to insinuate that I like all things about the Stampers but I know only too well aspects of this tribe and I've been fascinated how they all come to terms with their rather sad lives.

It doesn't hurt that the colorful story, full of machismo and hurt and angst, stars Paul Newman and Henry Fonda with the ever-reliable Lee Remick, lanky Michael Sarrazin, and blond, muscleman, character actor Richard Jaeckel in his finest role.

The Stampers are long-term loggers who live on a compound on a small island that can only be accessed by boat. When folks arrive across the river, they ring a bell or yell out and a Stamper comes and collects them. As the story opens the local logging conglomerate is honoring a strike while the independent Stamper family thumbs its scab noses at the strike and the townsfolk while invoking their ire. (The fictional town, by the way, is called Wakonda, spelled differently but pronounced the same as it is in Black Panther. You read it here.)

I expect for many the kick of this flick is the exciting and well-drawn logging sequences but for me the family scenes, particularly those around the dinner table, are just so sad and touching and memorable. What follows, until the last seven paragraphs, is a giant spoiler alert...

Fonda plays the head of the clan, Henry Stamper, a contrary, stubborn, sassy-mouthed widower who delights in putting people down. Of course he reserves most of his cruelty for his family... most of whom slough it off. Henry is laid-up with half an upper body cast because he fell out of a tree. The inactivity is making him more disagreeable than ever. He has long been known to espouse his life-long, favorite expression, never give a (sic) inch, when he needs to. Henry never gives in.

His son, Hank (Newman) has been standing in for Henry on the job since the accident. He has a penchant for his father's mean-spiritedness but perhaps because laughter comes easier to him and he's more of a kid than his old man, we may excuse him more.

That's what his wife Viv (Remick) has been doing. We can tell by her downbeat behavior that she's tired of making excuses for the man who whisked her off her feet and made her feel loved and then brought her to the family compound and virtually ignored her while she is worked to death cooking, cleaning, doing the wash and keeping her mouth shut. It could be argued that the actress doesn't have a lot to do in the film or a lot to say but we clearly see her repression through her restrained acting.

Then there's Leland (Sarrazin), Henry's youngest son and Hank's half-brother who just shows up one day after being gone for 10 years. He's just recovered from a suicide attempt and has, in fact, run away from where he lived because of unpaid bills. Father and brother pick on him unmercifully... it's good sport to rough-up and humiliate someone who is feeling weakened.

Every character who comes across Leland caustically mentions his long hair. No one is worse than his old man who says he lost his son who comes back a daughter. If that's not enough he tries out that he looks like some kind of New York fairy. Henry refers to a number of men as campfire girls and sissies. He is not as loud and obvious about his misogyny (to try to prove his point on how easy something is to figure out, he says even a dumb-fool woman could do it) as he is his homophobia or his accusations that union people and others of like minds are pinkos. As objectionable as this is, I always had to stifle a giggle knowing the Stampers are right-wingers being played by some of Hollywood's most famous liberals.

Four more Stampers live in the big house... cousin Joe Ben (Jaeckel), his wife Jan and their son and daughter. Joe Ben is the only truly happy camper in the entire film. He has found God which has enabled him to stay away from the family's seedier aspects and he is kind and respectful, fun and funny. Wife Jan (Lawson), while nice enough, doesn't say boo.

Both women serve the men and then keep quiet, even sitting at the end of the long table by themselves. When Viv serves something to Leland, he thanks her and one can see she is almost shaken by the kind acknowledgment. Viv had to smile when she hears Leland say to the other men don't the ladies ever get to say anything at breakfast?

Of course this is primarily a man's world and it is about man's work. If women here are given short shrift, I expect it's no different in real life. One can only wonder why they put up with it.

There are moments of comedy to relieve the seriousness, such as a motocross-type race, a brawl, dynamiting, and just some funny lines but there are two scenes I found so touching, each of them in their own ways hard to watch.

The first is when Viv finally speaks up as she begs Hank to stay home from the day's work and like we used to, maybe after cleaning up the morning dishes we can make love. We know he could do it if he wanted to but because he doesn't respond right away, she moves over to her father-in-law who is on his way out. She begs him to stay home as well, saying everyone could use a day off. Crusty ol' Henry dismisses her with his mantra that they must all keep going. He says we work, sleep, screw, eat, drink and keep going... it's all there is. Or as she knows, never give a inch. When she turns back to Hank, he has disappeared.

When I did the posting earlier on Richard Jaeckel, I mentioned one of the most unforgettable scenes in the movies... the drowning death of his character Joe Ben. Of course it would have to be the nicest character in the film to make it even more heart-breaking. A mishap on the hillside sends a huge tree into the water and on top of him and pins him under the water except for above his upper chest.

Hank tries everything he knows to help get him out. Both men expect as the tide comes in, it will loosen the log and free Joe Ben but, of course, that doesn't happen. One shift pins him under to some place around his lower lip and at eight minutes into the scene, another shift causes him to go underwater. It still took three more minutes to lose him but before that happens, an overhead shot allows us to see Joe Ben clearly under... at first joking and then stillness. That moment is particularly haunting.

On that same day, Henry's arm is amputated and then he passes away. When Jan gets word that her beloved husband has died, she packs up the kids and leaves as well. And then, still on the same day, Viv leaves. She finally realizes she's less important to Hank than she had hoped. Amusingly she says she probably could have picked a better day and she does it while her husband is still at the hospital.

Leland asks her if she wants him to come with her and she says she thought about that but says she is not what he needs. Their scenes together are tender but also awkward. In the book the pair have an affair and it was also filmed to include that but then was cut out. What remains is awfully chummy without being addressed.

I liked, even appreciated, the lighter ending. It is comical and somewhat uncertain for the two brothers but it's what it needs to be. It shows them running logs down the river in a series of four connected rafts and pulled by the family's small tugboat. The still- aggravated residents gather on the banks to yell insults at them. Hank climbs to the top of the boat's smokestack and affixes Henry's amputated arm to the top with the middle finger extended.

Sometimes a Great Notion began as a rather troubled project when director Richard Colla was fired. He apparently saw the project a bit differently than the producers, Paul Newman and John Foreman. After trying to get someone else and failing, it was decided that Newman would direct. It was only his second time directing and the first time in a film in which he would also star. He was nervous about that aspect but as I see it, he did fine.

John Gay fashioned a screenplay out of Ken Kesey's second novel but the first to become a film. His first novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, became a film four years after this one. Kesey's 600-page Stamper story likely would have been better as a multi-part miniseries. (It's not too late.)

I have never agreed with some who claim the screenplay never catches fire. I see it as being somewhat old-fashioned but say that in the best possible way. Someone once told me nothing ever happens and I told him he must have seen another movie. Still, I am aware that it had a hard time finding an audience. It did become the first movie ever shown on HBO and later on network television, in the hope of gathering a bigger crowd, it was retitled Never Give an Inch. In later years it has found an audience.

The actors all turned in good performances although my favorite is Jaeckel who earned his only Oscar nomination. His wife in the film, Lawson, was actually the wife of producer Foreman.

Bravo to Newman on the logging sequences, too. He creates a reality that allows viewers to see what a colorful, exciting, dangerous and butch experience it is.

Contributing to the overall success is Richard Moore's exciting Technicolor camerawork, Henry Mancini's stirring musical score and the rousing Charley Pride song All His Children, sung over the opening and closing credits.

Here's the trailer:

Next posting:

From the 60s

No comments:

Post a Comment